The Irish Soldier in 1918

Commandant Lar Joye

On 21st March the German Army attacked on the Western Front in a last attempt to win the war before American divisions arrived. The attack was fast and fluid, using specially equipped soldiers called stormtroopers. The allies held on, eventually counter-attacking all along the line. The German Army was overwhelmed and requested an armistice, which went into effect on November 11th, 1918. When Europe went to war in 1914, Ireland (as part of the British Empire) was automatically involved. Over the course of the war, about 150,000 Irishmen volunteered to fight in the British Army. Indeed, the Irish people from 1914 to 1923 endured ten years of intense military activity, World War One, an Urban Insurrection, a Guerrilla War and finally a bitter Civil War.

The Result was a new nation bearing both the hopes of many of its citizens, and the pain left by the wars that had brought it into being. In 1918 two Irish Divisions, the 16th (Irish ) and 36th (Ulster) Divisions bore the brunt of the German attack in March 1918, the 16th was effectively wiped out and when it was relieved on 4th April had suffered 7,149 casualties and was reorganised with only one Irish Battalion, 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers. There was also Irish involvement in regiments from Australia and Canada and even New York.

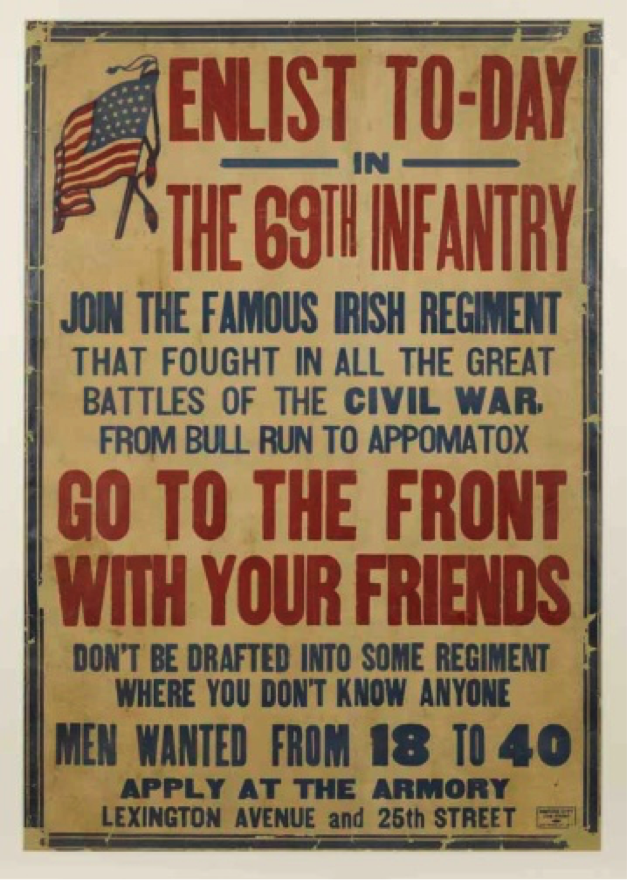

The 69th Regiment whose regimental motto was ‘Gentle When Stroked, Fierce When Provoked’ and had earned the nickname the “Fighting Irish” during the US Civil War (1861-65) was a National Guard unit that fought in the war The United States of America entered the war on 6th April 1917 and by the summer of 1918 over 2 million American soldiers had landed in Europe and was a key factor in the Allies winning the war. For the First World War the 69th Regiment enlisted 3,600 men organiz sed into 3 battalions. A recruiting campaign started with posters encouraging Irish men to join and 95% of the regiment was Irish and Roman Catholic. The 69th Regiment was part of the 42nd (Rainbow) Division which consisted of the best units of the National Guard and was for a time commanded by General Douglas MacArthur. The Regiment went into action on 27th February fighting alongside the French Army and took part in fierce fighting as the war drew to a close through 7 battles loosing 644 men. Among the well know members of the regiment was Father Duffy their revered Chaplin and a stature of him was erected in Times Square in his honour when he died in 1932. The most famous officer was Lieutenant Colonel ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, who won a Medal of Honour as did 2 other members of the 69th Regiment.

sed into 3 battalions. A recruiting campaign started with posters encouraging Irish men to join and 95% of the regiment was Irish and Roman Catholic. The 69th Regiment was part of the 42nd (Rainbow) Division which consisted of the best units of the National Guard and was for a time commanded by General Douglas MacArthur. The Regiment went into action on 27th February fighting alongside the French Army and took part in fierce fighting as the war drew to a close through 7 battles loosing 644 men. Among the well know members of the regiment was Father Duffy their revered Chaplin and a stature of him was erected in Times Square in his honour when he died in 1932. The most famous officer was Lieutenant Colonel ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, who won a Medal of Honour as did 2 other members of the 69th Regiment.

When we look back at the Irish contribution to the war, World War One had started optimistically in the summer of 1914, many believing it would be over by Christmas. There were 70,000 Irish soldiers and 14 Irish Regiments in the small British Army, the last regiments created after the Boer War in 1901: Irish Guards, South Irish Horse and North Irish Horse. Most of the Irish Regiments were serving in India when the war broke out with a Depot back in Ireland recruiting for permanent battalions and the training the militia regiments. The Territorial Army did not extend to Ireland.

Recent research has shown that there was general support for the war in Ireland in particular in cities like Dublin which had high levels of unemployment and was still recovering from a large industrial dispute between employers and workers called the Lockout in 1913. The political situation in Ireland had been dominated for the previous 30 years about whether Ireland would obtain Home Rule, a form of limited self-rule from United Kingdom. This was opposed by many Protestants based in the 4 Northern Counties but also in Dublin which was the centre of government power in Ireland. Most historians agree that by 1914 Ireland looked like it was on the cusp of Civil War between two militias, the Ulster Volunteer Force and Irish Volunteers, now consisting over 300,000 men. However the outbreak of the war meant the suspension of the Home Rule Act for its duration and the immediate response from the leading politicians of the time was to support the war and encourage the volunteers of both militias to join the British Army. In the case of Irish Nationalists the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party was John Redmond who caused a split in the Irish Volunteers by encouraging them to join the British Army. 11,000 remained in the Irish Volunteers and the majority following Redmond into the Irish National Volunteers or into the British Army.

As part of the British Expeditionary Force, Irish soldiers were sent to support the French Army, this included 4 Irish cavalry regiments and 9 infantry regiments. By the end of the war 150,000 Irish men had volunteered to join the British Army and about 35,000 men died. Due to the political situation in Ireland conscription was never introduced in Ireland. During the war the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Regiment (RDF) raised a total of 11 Battalions, smaller than a British regiment and reflecting a highpoint of recruitment from August 1914 to March 1916, before the 1916 Rising. The Battalion’s served as follows:

- 1st RDF took part in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 as part of the 29th Division.

- 2nd RDF arrived in France in the summer of 1914 as part of 4th Division

- 3rd (Reserve), 4th (Extra Reserve) & 5th (Extra Reserve) RDF were mobilised on 4th August 1914 at Naas and Dublin. These battalions served variously in Ireland, England, Wales and Scotland during the war.

- 6th & 7th RDF took part in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915 as part of 10th Division

- 8th & 9th RDF arrived in France in December 1915 as part of the 16th Division

- 10th RDF arrived in France in August 1916. It first served in the Naval Division before transferring to the 16th Division

- 11th RDF was formed at Dublin in July 1916 and by Jan 1918 it was located in Aldershot. It never fully recruited due to the changing political situation at home

By the end of the war 4777 soldiers of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers had died consisting of 269 officers and 4508 NCOs and men.

At the Divisional level 3 Irish Divisions, 10th, 16th (Irish) & 36th (Ulster) Divisions were created in 1914 to fight in the war. The 10th would be the first to go to war in the summer of 1915 in Turkey at Gallipoli, while 16th & 36th Division would fight on the Western Front from 1916 to 1918.

The war in 1915 was characterised by the politicians’ desire to open a new front to break the stalemate in France. Today it is popularly remembered as an Australian war, while the Irish contribution is largely forgotten; 15,000 Irish men served there from April to December 1915 and it is estimated that 3,500 died there. In August 1915 the 10th (Irish) Division landed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The troops fought bravely, but failed to capture the high ground needed to break the stalemate; the 10th Division was essentially destroyed within two months. The 7th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers was part of the Division and they included a Pals Company made up of rugby players or those who had gone to rugby playing schools. D Company was quickly nicknamed “the Toffs in the Toughs” and trained at the Royal Barracks now Collins Barracks Dublin from February to April 1915. Two hundred soldiers of D Company sailed from Dublin, they landed at Sulva Bay on the Gallipoli Peninsula on 6th August and— within a week of arriving, 131 were dead or wounded,

By 1916 the optimism of the earlier part of the war had now disappeared and recruitment was beginning to fall. Conscription was introduced in Britain in January 1916 but not in Ireland as it was seen as too difficult to implement. 1916 was the year for Ireland when the crucial event of Ireland’s ten year ordeal was to happen. A relatively small but determined group of Irish men and women took the opportunity offered by Britain’s conflict with Germany to strike a blow for Irish independence in Easter 1916. The newly proclaimed Irish republic was quickly and brutally suppressed, but the memory of the heroism and of the executions that followed, changed Irish history forever and how Irish soldiers who fought in World War One were remembered.

1916 was to be a significant year for the British Army it was the first year were their small professional army had been expanded into a large volunteer army capable of going to war. It had taken almost 2 years to create it and for most of the soldiers it was their first battle and the remaining two Irish Divisions, 16th & 36th also went to war for the first time in 1916. Irish involvement is normally associated with the soldiers of the 36th Ulster Division on 1st July however it is often forgotten that the battle lasted for 5 months until November and the Irish soldiers in 16th (Irish) Division fought there during the Battle of Ginchy in September 1916. This Division took the village of Ginchy at a cost of over 4,000 dead and wounded. Among the dead was Irish MP, poet and nationalist Tom Kettle, who, just before he died wrote:

‘I have seen war, and faced modern artillery, and know what an outrage it is against simple men’.

Tyneside Irish at the Somme

Several other Irish units took part that day including the 103rd Tyneside Brigade which consisted of 3,000 Irishmen in a Pals Regiment from Newcastle. This group were one of the few to be photographed walking towards the German lines before suffering terrible casualties, indeed the most of any Irish unit.

In 1917, the two Irish Divisions fought side-by-side, in victory and then in defeat. In June 1917, the 36th (Ulster) and 16th (Irish) Divisions benefited from careful preparation and good luck to eject well-entrenched German forces from the important Messines Ridge. The preliminary artillery bombardment was unprecedented in its intensity – three shells exploded on the German lines every second for 12 days. Two months later, the same two divisions suffered terrible casualties in assaulting concrete fortifications amid the mud of an unusually wet autumn. Despite warnings from his officers, the Army commander, Irishman Hubert Gough, insisted the attacks go ahead. An observer later wrote: ‘The two Irish divisions were broken to bits, and their brigadiers called it murder’.

During the war both sides struggled to hang on in the face of unprecedented casualties and repeated failures to break through the Front Lines. Now individual soldiers fought in order to support their comrades, rather than pursue great causes. In this bloody contest, the side that held out the longest would be the winner. 1918 saw the introduction of a Combined Arms approach to war; Allied soldiers fought alongside tanks and planes, supported by creeping artillery barrages. This new approach along with American reinforcements allowed the Allies to win. For the the 36th (Ulster) and 16th (Irish) Divisions the battles of 1918 were to prove equally as costly the previous years and after 3 years of fighting on the Western Front, total casualties, that is killed, wounded and missing were 28,400 for 16th Division and 32,000 for 36th Division.

For Ireland, World War One and the 1916 Rising had changed the country for ever and a War of Independence would break out in 1919 followed by the splitting of the country in 1920 and a Civil War in 1922. Over 100,000 Irish soldiers who fought in the British, American, Canadian and Australian Armies would return to Ireland to a different country from the one they had left.