Ernest Fitzroy was born in 1917 in Galway to banker Charles Eric Blake Knox. Charles’ wife, Audrey Prudence, was the daughter of Major Harry D’Esterre Darby Dowman of the Royal Engineers who had fought in WWI. The couple chose to give their baby the middle name ‘Fitzroy’ in admiration of a relative – Vice Admiral Robert Fitzroy – best known as the Captain of the HMS Beagle on which the naturalist Charles Darwin sailed to gather material for his theory of evolution. Robert Fitzroy is also credited with founding the Meteorological Service or the Met Office as we know it.

Ernest was the second of four children, the youngest a girl. Completing his education in Galway, Ernest joined the army and was sent for officer training to Sandhurst Military Academy. Upon passing out, he was assigned to the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

When he was 22 years old, Ernest met Phyllis Humphries May, daughter of William May, warehouseman in a woollen mill in Londonderry. Three of the Mays’ sons had distinguished careers. The eldest, William Morrison May, was elected to Parliament and eventually became Minister of Education. The second son, Isaac Allen May, served in India with the Royal Ulster Regiment, rising to Colonel and remaining in the subcontinent until the Independence of India in 1947. After Isaac, came Thomas Eric who also joined the Royal Ulster Regiment and went to India. A linguist, who spoke fluent Hindi, and a skilled rider and polo player, he fought in the Burma war of 1944 and had the unique distinction of being awarded the Military Cross on the battlefield in Kohima.

Phyllis May was born in Belfast but had boarded at school in County Wicklow and was a frequent visitor to Dublin. Ernest married Phyllis in Omagh, County Tyrone, in 1941. After a mere six weeks, Ernest was forced to leave his young bride when his battalion boarded a troop ship bound for India.

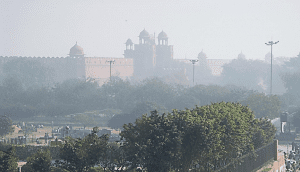

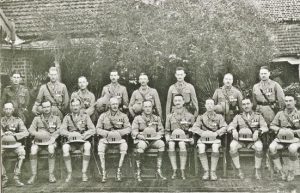

Arriving in India, eight of the young men proudly posed with their Commanding Officer in front of the Red Fort in Delhi. Ernest Fitzroy referred to these men as ‘my brothers’. The battalion was lucky its first posting was in the cool of the hills of Wellington, rather than the heat of the plains.

The town of Wellington sat on a plateau in the Nilgiri Hills (Tamil Nadu). Originally called Jakkatalla, the town’s name was changed in 1860 in honour of the Iron Duke. The green and hilly region is the site of India’s Defence Services Staff College and vies with Ootacamund (dubbed Snooty Ooty) for position as the best hill station in the Nilgiris.

Here, in comfortable Wellington Barracks, the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers presented their colours and tried to adapt to their new environment and routine. The following year, war was declared and the threat of a Japanese invasion of Burma loomed.

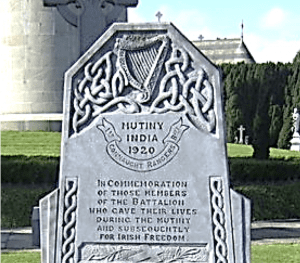

The battalion’s immediate order was to go to Meerut (Uttar Pradesh) in north India – a long way from southern Wellington. Meerut was best known for igniting the flame that started the raging fire of the Indian Mutiny of 1857. In this historic cantonment, the RIF trained in jungle warfare as the Japanese invasion of Burma became a reality. The Japanese invaded Burma in January 1942. Two months later, the 1st Battalion was airlifted from Dum Dum, near Calcutta, to Burma and initially joined the 13th Indian Brigade. However, during the course of the war, the Inniskillings were forced to adapt to the reorganisation of formations several times. During the relentless attacks, Ernest witnessed the horrific death of his best friend at Japanese hands. He wrote to his wife saying he had seen a terrible thing and would never be the same again.

Not surprisingly, the Arakan Campaign, led by the 14th Indian Division, failed. Ill-equipped and weak from repeated defeats and sickness, the battalion joined the retreat to the Indian border by foot, motorcar and ferry. On this three-month-long journey, Ernest fell victim to a Japanese mortar bomb. His life was saved by an American missionary doctor in a field hospital. But dysentery, hookworm and malaria continued to plague him and his fellow soldiers. Under constant attack by the Japanese, he was shot twice and so badly wounded that he was not expected to live. After recuperating in India, he was sent back to Burma. Taken prisoner by the Japanese, Ernest endured torture and maltreatment, until freed by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army.

Returning to India after the war, the 1st Battalion was stationed in Dehradun at the Tactical Training Centre. Situated at the foothills of the Himalayas, it was the perfect base for weary soldiers to recover from the horrors of war. Between constant bouts of malaria, Ernest managed to travel a bit. He is known to have taken a train to Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh) and believed to have shaken the hand of Mahatma Gandhi.

Ernest Fitzroy made a brief trip back to Ireland in late 1945, before spending several months in a military hospital in Scotland. X-rays showed bits of Japanese shrapnel still lodged in his chest. He finally came home in 1946 and attempted to pick up life where he had left it. He joined the Burma Star Association where he met other veterans of that horrendous war. But despite having three children with Phyllis, life could never be the same again (as he had predicted to Phyllis in a letter from Burma). The pair separated and Phyllis returned to Northern Ireland, living first in Belfast and then Newry.

Ernest Fitzroy worked for Kelly’s, the main distributor of Morris cars. Based in Waterford, Mr J Kelly’s garage was the sole agent for the cars in Ireland. Ernest met Gladys Kelly, a widow (who may have been related to the garage owner), and shared his life with her in Clarinda Park, Dun Laoghaire. A tortured soul, Ernest had contemplated suicide on several occasions and even bought a burial plot for himself in Deansgrange Cemetery. Gladys died in 1992 and was buried in the plot Ernest had bought for himself all those years ago. He ‘soldiered on’ until 2008 when he died peacefully in St Michael’s Hospital in Dun Laoghaire. He shares the grave with Gladys.

Phyllis lived for another four years, dying just before Christmas in the seaside resort of Kilkeel in County Down.