Surgeon John George Collis M.D.

1845-1877

The internet threw up so many John George Collis’ that sorting one from the other took some time but I eventually found the right man.

John George Collis’ father, Peter, was a Captain in the 95th Regiment – one of six regiments to bear the number 95. Peter’s was the 95th (Derbyshire) Regiment of Foot, raised in 1823. After the Crimean war, it was heading for South Africa, when those rebellious sepoys began to play up and the regiment was diverted to India to quell the Mutiny of 1857. It won a Victoria Cross for helping to recapture two stations in central India from the rebels and remained in India until 1870. Upon its return to England, it was merged with Sherwood Foresters, as its 2nd Battalion.

There is nothing to suggest Peter ever served in India. He retired a captain, so he could not have been in the army for long.

His son, John George, was born in Mountford Lodge, Fermoy, Co Cork on April 16, 1845 and was the third of four Collis children. He probably earned his medical degree in Ireland and was 29 years old when the Queen was pleased to approve his admission to Her Majesty’s Indian Medical Service. Collis was appointed surgeon in 1873 and joined the Madras Native Infantry. (At one point he served in the same station as Surgeon Major James Sadler Riding, whom I will be writing about later.)

INDIAN MEDICAL SERVICE

The Honourable East India Company initially needed medics for its long sea voyages. Over time, sea surgeons found ministering to the needs of Indian royalty and various courts was a lucrative sideline. This led to the HEIC appointing a Surgeon-General in 1816.

If the internet is to be believed, the first three incumbents were sacked for embezzlement, drunkenness and debauchery. Eventually the three Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay established their own medical services. With fixed grades and rules, they were less likely to attract swindlers, swiggers and libertines.

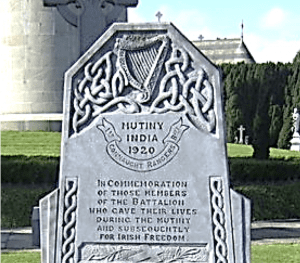

They united to form The Indian Medical Service after 1857 so perhaps the Indian Mutiny had some bearing on the formation of the IMS. Although basically a military organisation, its surgeons served in army and civilian hospitals, until India’s independence in 1947.

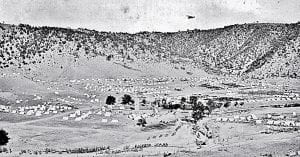

Six years later, Collis moved to the idyllic island of Andaman and was stationed in Port Blair.

But the name of the island struck terror in the hearts of the unfortunate Indian convicts ‘transported beyond the seas with irons and labour’ and exposed to disease and torture. It was known as Kala Pani (Black Water).The Cellular Jail’s 693 cells made up the seven spokes, each three storeys high, radiating from a central tower. The tiny cells were designed for solitary confinement, each looking out on the windowless back wall of the next spoke.

Beside the fortified entrance, a smaller building served as a prison hospital. This could be where Collis worked, treating prisoners for one of the many diseases that were rife at the time, due the swampy and densely vegetated environment – malaria, measles and the dreaded Andaman Fever (and torture wounds?).

Perhaps Collis fell victim to one of the diseases himself for he died in Port Blair and the age of 32.

His mother, Elizabeth Mitchell lived in Stillorgan Park until her death in 1884, so that explains why Surgeon John George Collis is remembered on a grave in Deansgrange Cemetery, Dublin.

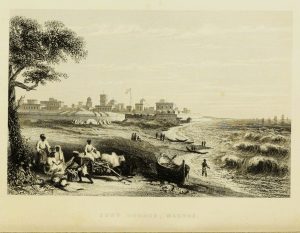

THE ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS

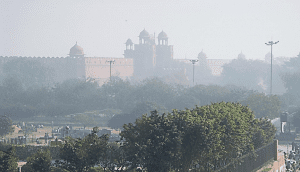

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands lie in the Bay of Bengal between India; and Burma and are part of the Union Territory of India. A small part of the archipelago belongs to Burma.

They were mainly inhabited by tribes – Andamanese, Jarwas, Sentinelese, Onges, Nicobarese and Shompens – reputed to be naked cannibals.

The Marathas kept the British out of the islands for as long as they could until it was finally colonised.

In 1789 a naval base and penal colony was established in Port Blair, named after Lieutenant Archibald Blair of Bombay Marine, who founded it.

Port Cornwallis (named after Admiral William Cornwallis) was a handy haven for ships carrying troops to the Burmese war of 1824.

During WW2, the islands were briefly captured by the Japanese in 1942, who promptly released the inmates of the cellular jail, before quickly filling it up again. They shipped British POWs to Singapore and then began freely swinging their tachis at the local population.

Later, during the struggle for Independence, the dreaded Cellular Jail became a repository for many Indian freedom fighters. Upon the Independence of India the penal settlement was abolished and the islands became a Union Territory of India. The jail reincarnated as a museum.

Today, the islands are a paradise for honeymooners and surfers – a far cry from its grisly past.

Unfortunately, the indigenous peoples of the islands have been reduced to double figures.

MILITARY CONNECTIONS

John George Collis was also linked to the army via his relatives, although none served in India.

The eldest of the family was Elizabeth Martha, who never married and died in Berry (in Australia?). I could not find out much about younger brother, Edward Peter, who was born four years after John George and died, unmarried, at the age of 38.

Older brother, William Gun (great name for a military man), was born two years before John George, in 1845. He joined the Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment in 1864 and was Adjutant for 9 of his 28 years of service. Although the 4th and 5th Battalions were stationed in India for some years from 1914 on, there is no proof that Collis was ever posted there.

Collis married Mabel Katherine Robson whose father was a Captain in 5th Dragoon Guard. The couple had three children and seemed to have ended their days in Barrymore Lodge, Castleyons, County Cork. Today, Barrymore Nursuries run a successful business from the property.

William Gun and his wife are buried in St Nicholas’ Cemetery in Cork.

Their son, William Henry joined the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. His short life ended in May 1917 when he was killed in Flanders. He is remembered on the War Memorial Heroes column in St Finbarr’s Cathedral, Cork.

Younger son, John George (not to be confused with many other John Georges, including his uncle), joined his father’s regiment. He, too, had a short military career, retiring as Captain in 1919 but remaining on the Active List.